Why Taskgroup and Timeout Are so Crucial in Python 3.11 Asyncio

Embracing Structured Concurrency in Python 3.11

In last year’s Python 3.11 release, the asyncio package added theTaskGroup and timeoutAPIs. These two APIs introduced the official Structured Concurrency feature to help us better manage the life cycle of concurrent tasks. Today, I’ll introduce you to using these two APIs and the significant improvements Python has brought to our concurrent programming with the introduction of Structured Concurrency.

New Features of The Python 3.11 Asyncio Package

TaskGroup

TaskGroup is created using an asynchronous context manager, and concurrent tasks can be added to the group by the method create_task, with the following code example:

async def main():

async with asyncio.TaskGroup() as tg:

tg.create_task(some_coro(1))

tg.create_task(other_coro(2))

print("Both tasks have completed now.")When the context manager exits, it waits for all tasks in the group to complete. While waiting, we can still add new tasks to TaskGroup.

Note that assuming that a task in the group throws an exception other than asyncio.CancelledError while waiting, all other tasks in the group will be canceled.

Also, all exceptions were thrown except for asyncio.CanceledError will be combined and thrown in the ExceptionGroup.

Timeout

asyncio.timeout is also created using the asynchronous context manager. It limits the execution time of concurrent code in a context.

Let’s assume that if we need to set a timeout to a single function call, it is sufficient to call asyncio.wait_for:

async def main():

await asyncio.wait_for(some_coro(delay=2), timeout=1)But when it is necessary to set a uniform timeout for multiple concurrent calls, things will become problematic. Let’s assume we have two concurrent tasks and want them to run to completion in 8 seconds. Let’s try to assign an average timeout of 4 seconds to each task, with code like the following:

async def main():

await asyncio.wait_for(some_coro(delay=5), timeout=4)

await asyncio.wait_for(other_coro(delay=2), timeout=4)You can see that although we set an average timeout for each concurrent method, such a setting may cause uncontrollable situations since each call to the IO-bound task is not guaranteed to return simultaneously, and we still got a TimeoutError.

At this point, we use the asyncio.timeout block to ensure that we set an overall timeout for all concurrent tasks:

async def main():

async with asyncio.timeout(delay=6):

async with asyncio.TaskGroup() as tg:

tg.create_task(some_coro(delay=5))

tg.create_task(other_coro(delay=2))

print("All tasks have completed in time.")What is Structured Concurrency

TaskGroup and asyncio.timeout above uses the async with feature. Just like with struct block can manage the life cycle of resources uniformly like this:

def main():

with open("hello.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("hello world.")But calling concurrent tasks inside with block does not work because the concurrent task will continue executing in the background while the with block has already exited, which will lead to improper closure of the resource:

async def file_coro(f):

await asyncio.sleep(5)

f.write("hello world.")

async def main():

with open("hello.txt", "w") as f:

# This will result in nothing being written to the file

asyncio.create_task(file_coro(f))

# Do some other things.Therefore, we introduced the async with feature here. As with, async with and TaskGroup Is used to manage the life cycle of concurrent code uniformly, thus making the code clear and saving development time. We call this feature our main character today: Structured Concurrency.

Why Structured Concurrency Is So Important

History of concurrent programming

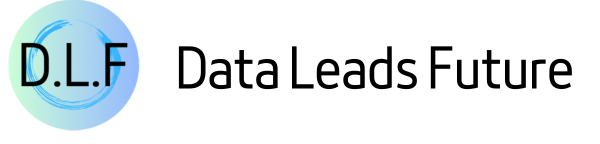

Before the advent of concurrent programming, we executed our code serially. Code would perform for_loop loops, if_else conditional branches, and function calls sequentially, depending on the order in the call stack.

However, as the speed of code execution became more and more demanding in terms of computational efficiency and as computer hardware developed significantly, parallel programming (CPU bound) and concurrent programming (IO bound) gradually emerged.

Before coroutine emerged, Python programmers used threading to implement concurrent programming. But Python’s threads have a problem, that is, GIL (Global Interpreter Lock), the existence of GIL makes the thread-based Concurrency unable to achieve the desired performance.

So asyncio coroutine emerged. Without GIL and inter-thread switching, concurrent execution is much more efficient. If threads are time-slice-based task switching controlled by the CPU, then coroutine is the creation and switching of subtasks back into the hands of the programmer himself. While programmers enjoy convenience, they also encounter a new set of problems.

Problems with the concurrent programming model

As detailed in this article, concurrent programming raises several issues regarding control flow.

Concurrent programming is opening up multiple branch processes in our main thread. These branch tasks silently perform network requests, file accesses, database queries, and other duties in the background.

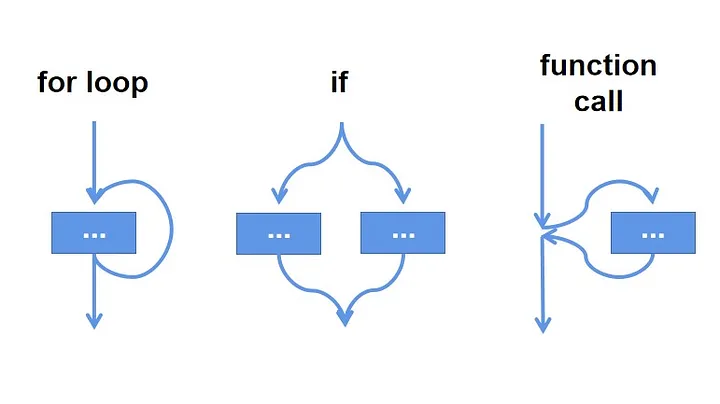

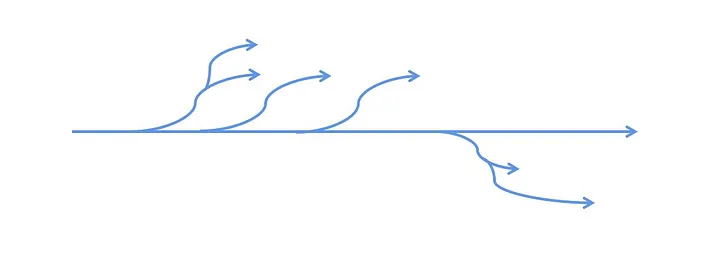

Concurrent programming will change the flow of our code from this to this:

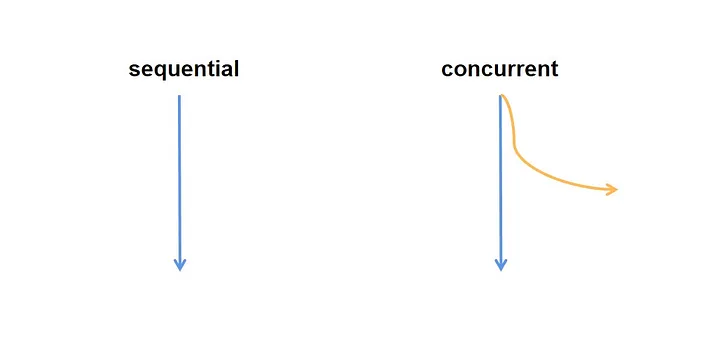

According to the “low coupling, high cohesion” rule of programming, we all want to join all the background tasks in a module together after execution like this:

But the fact is that since multiple members develop our application or call numerous third-party components, we need to know which tasks are still executing in the background and which tasks are finished. It’s more likely that one background task will branch into several other branch tasks.

Ultimately, these branching tasks need to be found by the caller and wait for their execution to complete, so it becomes like this:

Although this is not Marvel’s multiverse, the situation is now just like the multiverse, bringing absolute chaos to our natural world.

Some readers say that asyncio.gather could be responsible for joining all the background tasks. But asyncio.gather it has its problems:

- It cannot centrally manage backend tasks in a unified way. Often creating backend tasks in one place and calling

asyncio.gatherin another. - The argument

awsreceived byasyncio.gatheris a fixed list, which means that we have set the number of background tasks whenasyncio.gatheris called, and they cannot be added randomly on the way to waiting. - When a task is waiting in

asyncio.gatherthrows an exception, it cannot cancel other tasks that are executing, which may cause some tasks to run indefinitely in the background and the program to die falsely.

Therefore, the Structured Concurrency feature introduced in Python 3.11 is an excellent solution to our concurrency problems. It allows the related asynchronous code to all finish executing in the same place, and at the same time, it will enable tg instances to be passed as arguments to background tasks, so that new background tasks created in the background tasks will not jump out of the current life cycle management of the asynchronous context.

Thus, Structured Concurrency is a revolutionary improvement to Python asyncio.

Comparison with Other Libraries That Implement Structured Concurrency

Structured Concurrency is not the first of its kind in Python 3.11; we had several concurrency-based packages that implemented this feature nicely before 3.11.

Nurseries in Trio

Trio was the first library to propose Structure Concurrency in the Python world, and in Trio, the API open_nursery is used to achieve the goal:

async def main():

async with trio.open_nursery() as nursery:

nursery.start_soon(child1, 1)

nursery.start_soon(child2, 2)

print("All tasks done.")create_task_group in Anyio

But with the advent of the official Python asyncio package, more and more third-party packages are using asyncio to implement concurrent programming. At this point, using Trio will inevitably run into compatibility problems.

At this point, Anyio, which claims to be compatible with both asyncio and Trio, emerged. It can also implement Structured Concurrency through the create_task_group API:

import anyio

async def some_task(num: int = 0):

print(f"Task {num} running")

await anyio.sleep(num)

print(f"Task {num} finished")

async def main():

async with anyio.create_task_group() as tg:

for num in range(5):

tg.start_soon(some_task, num)

print("All tasks finished!")

anyio.run(main)Using quattro in low Python versions

If you want to keep your code native to Python to easily enjoy the convenience of Python 3.11 asyncio in the future, there is a good alternative, quattro, which has fewer stars and is risk-averse.

Conclusion

The TaskGroup and timeout APIs introduced in Python 3.11 bring us the official Structured Concurrency feature.

With Structured Concurrency, we can make concurrent programming code better abstracted, and programmers can more easily control the life cycle of background tasks, thus improving programming efficiency and avoiding errors.

Because of limited experience, if there are any omissions in this article about concurrent programming or Structured Concurrency, or if you have better suggestions, please comment. I will be grateful to answer you.